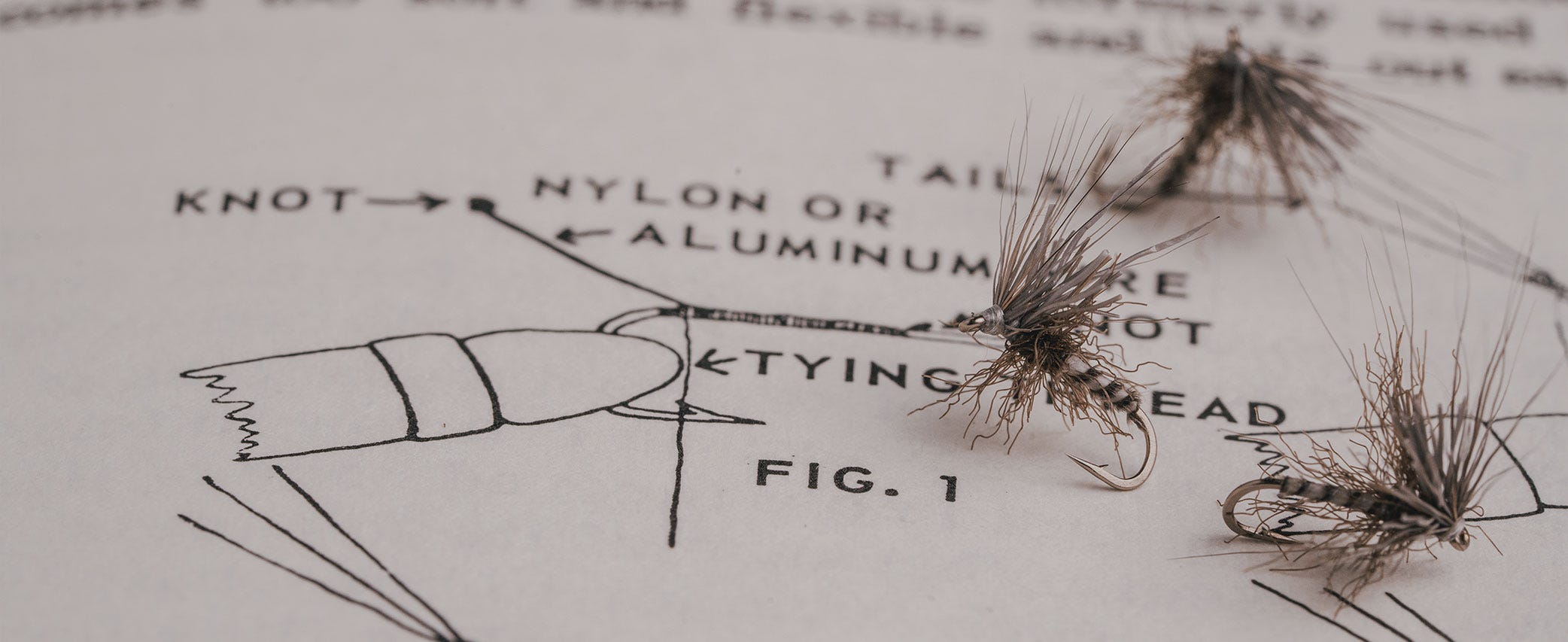

How To Tie The Honker Midge – The Best Midge Pattern I’ve Ever Tied

Words by Sam Wike

If you are a diehard dry-fly angler and fish the months of December through April, you know a certain angling truth: That is not a mosquito.

In fact, what you are seeing on the water are non-biting, two-winged midges of the Diptera order, and they make up a significant portion of a trout’s diet during a fish’s most challenging season—winter. What midges lack in size—most are matched by size-18 to 22 offerings—they make up in numbers. As these bugs stack up on the water by the thousands, trout may move into defined feeding lanes and inhale as many of those creatures as possible. Much of the feeding goes on below the surface as midge larvae turn into pupae and ascend to the surface. Once there they shed their shucks and become adults, riding the currents until they can fly away. Many don’t get that chance, because trout feed as heavily on adult midges as they do on pupae. Because of that, attentive and adventurous anglers can have some of the most productive dry-fly fishing of the season before most people have even dreamed about dipping their wading boots in the drink. And my go-to fly for this early season opportunity is the Honker Midge.

This is not an entomology lesson, but these are all the things I’ve considered in developing the Honker Midge over the past few winter dry-fly seasons.

Midges are pretty simple creatures having a long body with very distinguishable long legs. As mentioned, they are usually represented by flies in the size 18-to 22 range, sometimes larger and sometimes smaller. I fish on a slick-surfaced tailwater here in Montana and what I notice most, especially on calm days, is that only parts of a midge touch the water, those being the legs dimpling the surface and sometimes the rear of the body. When creating the Honker Midge, I knew I needed a dry fly that represented an adult midge barely breaking the surface tension. Fish can be picky when feeding on midges and I needed something that looked like the real thing.

Just to be clear, I’m not talking about an emerging midge or a spent midge, although once the Honker’s CDC wing is compromised, it absolutely gets eaten as a spent or emergent midge. Again, what I wanted was a match for adult midges riding those slick surface currents and clustering in the backeddies and sloughs. I found it the answer in tying the Honker.

I’ve been through many iterations of midge patterns, and some have worked. But most are hard to see, or they don’t float well, which is critical. In 20- to 40-degree (F) weather, sometimes colder, I don’t want to mess with a fly that won’t float long enough to get at least one eat before it’s toast. I even created a more durable deer-hair version of the Honker, that I think is great as an out-front fly ahead of a standard Honker. By employing the deer-hair version along with the standard Honker, I’m almost sure to always have a fly that floats.

So that’s it, the Honker is a simple midge, that’s extremely effective for two reasons: It creates the correct depression on the water and it floats well. As a bonus it’s an easy fly to tie.