Bulls: Born to Kill

The first bull trout I ever saw was spread across a cast-iron frying pan and had a bullet hole in its side, courtesy of a 30/06.

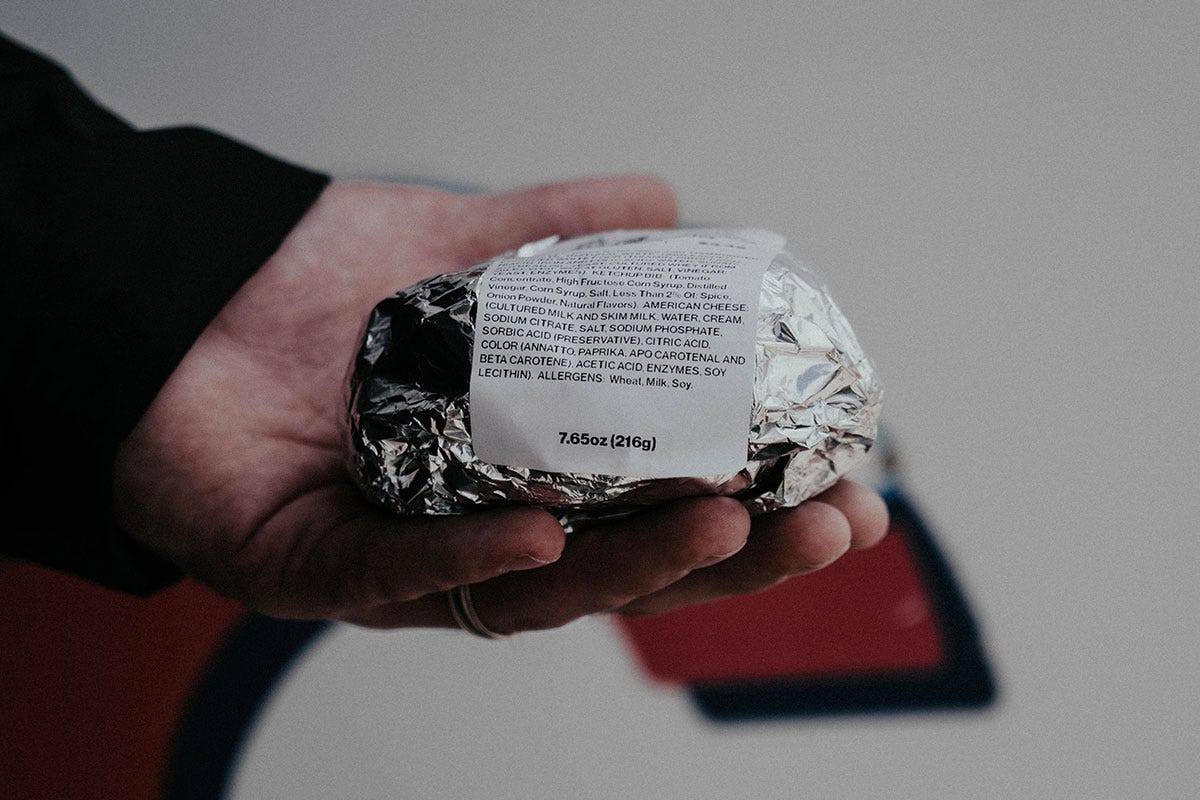

Granted, it was a friend’s photo of a bull trout and not the actual fish, but two things stood out: that bull trout’s head and tail greatly exceeded the width of the frying pan, and despite having a hole in its side there was still a lot of fish to eat.

I didn’t know at the time, but inland bull trout, until about the 1990s, were considered vermin and deemed a direct threat to more coveted fishes, including native cutthroats and non-native rainbow and brown trout. When anglers caught bull trout they often tossed them far up on the bank.

It was similar on the coast, where I grew up catching dolly varden (a very close cousin of the bull trout). Many anglers regarded those fish as a threat to Pacific salmon. I never tossed a dolly on the bank and I didn’t look kindly on that photo of a fish with a 30/06 slug in its side, but it wasn’t cancel culture at that time so I went ahead and forgave my friend for shooting a fish.

These days we both live and fish in Montana and his attitude toward bull trout has shifted completely, as has the general consensus among anglers; bull trout are now considered a worthy target deserving of their place in the ecosystem, and even though they don’t eat dries like a cutthroat, or jump like a rainbow, you can’t deny what the frying pan told us—bull trout are big.

Unfortunately, bull trout are also threatened in much of their native range and specifically targeting them on some Northern Rockies waters—especially in Montana—is forbidden. Oregon, Idaho, Washington and British Columbia (even Alberta), however, offer lots of opportunities to pursue bulls and you can do so on some of the most beautiful waters in the Pacific Northwest. Some of these waters are well known while others are tightly guarded secrets, as they should be.

Part of my fascination with bull trout is the research required to discover potentially unknown (or at least relatively unknown) fisheries. I scour documents, look at maps, talk to locals, interview biologists, and try to determine when and where my next great adventure takes place. Bull trout are highly migratory so they may be in one stretch of a river early in the season and somewhere else completely later in the year.

You can find bull trout in a variety of waters, ranging from broad rivers to tiny mountain creeks. In Montana I’ve located a small stream at the bottom of a deep canyon that holds native bull trout up to 14-inches long, and a few cutthroats of similar size. To reach the water it’s a long slog through heavy brush on a very steep slope that’s littered with downfall. It’s equally miserable climbing back out. But the fish eat dry flies, they are pure as can be, and you won’t catch a hook-scared fish. The banks are untrammeled and you could be the only angler to fish that stream in any given year.

The last time I “dropped in” I did so on a whim and without anyone knowing where I might be. Cell service was unavailable in the canyon and I’d forgotten my satellite GPS, which would have allowed me to send text messages if, for instance, I’d run into a grizzly (totally possible), been beat down by a moose (encounters are common), or slipped on a log or fell in a hole and broken a leg or ankle (a significantly high potential). I thought to myself, I could die down here. If you grew up in a family that seeks adventure and wild places, as I did, that’s part of the bull trout's appeal. I can be happy on, say, Idaho’s Henry’s Fork, where anglers fish in proximity and you might hear people saying, “What are you getting ‘em on?” So, I do like the scene. But fishing wild places that demand an effort to reach and treat you as if you own the water when you arrive, is every dedicated angler’s dream.

Not all bull trout waters are like that. Many have highways running alongside them; most are accessed by logging roads. One of those is the Columbia River near Golden, British Columbia. A couple yeas ago I cruised there during fall to fish the big river above Kinbasket Reservoir.

The Columbia holds bull trout from July through October and these fish range between a few pounds and 20 pounds or more. You can see the river from the road in many places (in fact it flows right through Golden) and access can be as easy as walking a few yards away from the truck.

I arrived in early October when the weather shifted overnight, from bright blue skies to rain, then sleet, then snow. I was fishing with a local guide who’d promised a steelhead-like fishing experience with two-handed rods, sink tips and streamers. With coastal and inland steelhead runs declining, any steelhead junkie would have to ask, Could bull trout be the new steelhead?

We started that morning at the mouth of a tributary where we hoped to find fresh bulls following kokanee salmon out of Kinbasket. We also expected to find fish backing down the Columbia, having spawned during summer and fall. They would be heading to the reservoir for winter.

I fished my gear just like I would for steelhead, low and slow with a long pause at the end of the drift. And I got nothing. Meanwhile, behind me, the guide was picking my pocket, hooking up on a couple fish I’d thrown over. I’m not a big fan of being bested on the water, so I stepped out of the river, checked my tippet and took my time selecting a different fly, one eye peeking at the guide. That’s when I saw the difference—the guide was twitching the fly through the prime water and stripping the fly on the down-hang. I cinched on a fly, waded back in, gave it some action, and had a four-pound bull in hand about 10 minutes later. This wasn’t exactly like swinging for steelhead, but it was close enough to offer the sensation that any cast could bring a 10-pound fish to net.

These bulls were what I’d expected, mostly three-to five pounds with large heads, strong jaws and a row of sharp teeth. Bull trout are keystone predators and built to kill. Whereas steelhead rarely feed when they enter freshwater, bull trout are always trying to eat something. Bulls are so aggressive, in fact, anglers often see these fish trying to take cutthroats or rainbows off the end of their lines. While this isn’t as dramatic as watching a hammerhead sever a tarpon in half, there’s definitely a primal feel to it.

The guide’s goal that season was to catch a 20-pounder and he was running out of time to do so. Several clients had them on, he said, but nothing made it to the net. The following day we pulled off the highway and drove down a long, muddy path, then crossed railroad tracks and dropped down a steep, wet, slippery slope to the river. This section of the Columbia is broad and fast. The guide and I walked downstream and when we reached the mouth of a creek he said, “They’re always right off this ledge.”

That afternoon we caught a half-dozen good fish. By the time it started to get a little dark we were soaked from our hike through the brush and four hours spent standing in a steady rain. We were just about at the end of the run. A hot shower, a steak, and a beer, was sounding better than sticking it.

I’d be leaving the following day and had already given up on the idea of catching a 20-pound bull. The guide admitted that the season was weird—he’d seen fewer fish than expected, they’d been in different places than he’d seen them before, and there’d been more angling pressure than he was used to. It sounded like the game was over.

Fortunately, I hooked up on a fish just before the end of the run and I knew right away this was a different beast. The fish made a run to the middle of the river and held steady in heavy current. I slowly wound that fish back to the bank. When its belly touched a rock it shot out to mid-river again. In that milky water I never actually saw the fish until it was in the net. It was pale gray, had white-tipped fins and subtle pink spots sprinkled across its sides. I can’t remember how many inches that fish measured, but the built-in net scale registered 14. 5 pounds.

While hiking back to the truck we crossed fresh bear tracks. It was dark now and I couldn’t tell for sure if a black bear or grizzly made those prints. It didn’t really matter because this was clear: somewhere nearby was an animal that could eat you. Wild places. Risk and reward. Trout as long as an arm. That is the appeal of western bull trout.